Christine de Pisan presenting her book to Louis of Orleans. British Library Harley 4431 f.095r, The Book of the Queen, Paris, France 1410-1414.

On Sunday, 27 April The Medieval Dress and Textile Society will host its annual conference online via Zoom. Attendance is free for members of MEDATS and tickets will be available through the end of the event. If you have recently joined the societies, please give the MEDATS volunteers at least a day to process your membership, then look for the access code by following the link to “recent emails you may have missed” in your membership receipt email.

All sessions will be recorded and made available to MEDATS members for two months following the event.

Programme

Abstracts of the papers below.

Session One – 11:00 UK (6:00 NYC)

Welcome

Ninya Mikhaila, Chair

Reconstructing a 16th century Embroidered Leather Hat

Robyn Spencer

Some Renaissance-style Head Coverings in Romanian Collections: ‘scuffie e rete d’oro’

Iuliana Dumitrascu

The Mystery of Wide-headed Women in 12th-century Illustrations

Dr. Indra Starke-Ottich

Break for Lunch or Breakfast – 12:30 UK (7:30 NYC)

Session Two – 13:30 UK (8:30 NYC)

Roses, Veils, Borders and Ribbons: the enigmatic headdresses of the Visitation group from the convent of St Katharinental

Katja Triebe

Powdered with Garters and Lined with Miniver: the importance of the hood as a part of the Garter Livery in the fourteenth and fifteenth Centuries

Dr. Chloë R. McKenzie

From the Phrygian Cap to the Turban: an impact of the Crusades upon representation of otherness

Dr. Tina Anderlini

The French Hood: royal and national identity in renaissance France

Emily Averiss

Short Break

Session Three – 15:30 UK (10:30 NYC)

Spectacles, their invention, spread and impact in the medieval period

Nick Boyle

‘Ane turatis for the quen’: the headdresses of elite women in late 15th century Scotland

Jenn Scott

The Late Medieval Chaperon in Documents: a first cut

Dr. Sean Manning

Ending – 16:45 UK (11:45 NYC)

Paper Abstracts

Reconstructing a 16th-century Embroidered Leather Hat

Robyn Spencer

Extant examples of early modern hats are uncommon, and most examples are a unique survivor of the type, yet a group of leather-covered men’s hats from the second half of the 16th century show a remarkable similarity of style, despite their different origins.

Three examples of such hats from Germany, Austria and Italy are now held in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, the Metropolitan Museum, and the Bagatti Valsecchi Museum. Although differing in detail, these hats share striking similarities of materials, construction and decoration. All are tall hats made over a stiff foundation such as felt, and covered with light coloured chamois leather, embroidered in black silk and adorned with an embroidered cartouche and a feather held in a leather cornet. Similar hats can be seen in the artwork of the time, worn by travellers.

This presentation tracks the recreation of a hat in this style, from initial research through patterning, sourcing materials, working the embroidery and completing the construction.

Some Renaissance style Head Coverings in Romanian Collections: ‘scuffie e rete d’oro’

Iuliana Dumitrascu

Very few items of clothing have been recovered from the tombs of the elites in the Romanian Principalities, most of which have been looted over time. Head coverings are extremely rare, and most hypotheses on their appearance are based on available iconographic sources – votive portraits in churches. Starting with two objects in the collection of the National Museum of Art of Romania, a bonnet (scuffia) and a hairnet (rette d’oro), both designed with gilded silver thread, I propose an overview of the regional consumption of these two specific types of luxurious head coverings inspired by European Renaissance fashion and imported into Wallachia and Moldavia, most probably via the Transylvanian commercial route, which connected central Europe with the Black Sea.

The manner in which these clothing accessories were worn by both men and women in central and southeastern Europe has been insufficiently studied; however, laboratory investigations of the last decades, which are now of critical importance during the restoration process of archaeological objects, have allowed us to obtain new information about materials and techniques for the realization of these fragile ‘copricapi’. In addition, digitization efforts of museum collections worldwide have made it possible to create a generous corpus of images that allows comparative analysis and brings new insights into the diversity of patterns and their geographical spread.

The Mystery of Wide-headed Women in 12th-century Illustrations

Dr. Indra Starke-Ottich

Many women in 12th century miniature paintings and sculptures were shown with a small face and a wide head, sometimes wearing a crown on top, that’s not even close to the face. In living history we’ve tried a lot of different veils over the past decades, but never really reached that visual effect. Finally a possible solution was seen in mosaics from the church of Monreale, Italy. They show some women wearing a turban without a veil on top, but having a silhouette very similar to the wide-headed women from other illustrations. Inspired from those mosaics, I have combined a turban with different types of reconstructed veils and capes and was able to recreate the head shape from a variety of illustrations. My practical experience is that a turban made to wear under a veil can easily be wrapped by one person without help and is comfortable to wear all day long. A comparison with details in illustrations from different countries leads to the conclusion that the turban was a common headdress in 12th century Europe and worn by nuns as well as noble ladies and peasants.

Roses, Veils, Borders and Ribbons: the enigmatic headdresses of the Visitation group from the convent of St Katharinental

Katja Triebe

At first glance, the Visitation group from the Dominican convent of St Katharinental (circa 1310–20) is characterised by its quality and grace. The opening of the figures’ wombs, which hold the unborn children of the two women, also attracts attention. However, on closer and comparative examination of the sculpture, another part is particularly surprising: the hairstyle and headgear of the holy women.

Veils with crossover appliquéd ribbons? A courtly maiden’s wreath for Mary? Open hair under the Gebende of the married Elisabeth?

The unusual head coverings are both unique to visitation depictions and peculiar to the labelling of a married and an unmarried holy woman. My paper will decipher these attributes in their courtly, cultural, theological and monastic context. It shows how they were meaningfully adapted to their patrons, who thus found in Mary and Elizabeth role models for their peers, for a virtuous virgin life in a convent.

Powdered with Garters and Lined with Miniver: the importance of the hood as a part of the Garter livery in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries

Dr. Chloë R. McKenzie

Founded in the wake of Edward III’s (1327-1377) victory at the battle of Crécy in 1346, the Order of the Garter was the embodiment of late medieval chivalric and military virtues. Intrinsically linked with the Hundred Years’ War, the Order was initially conceived as a means of unifying the noble and knightly classes through the formation of fraternal bonds of love and chivalry in order to aid Edward III in his pursuit of the French throne. Each year, the companions of the Order received robes at the expense of the King’s Great Wardrobe. There are few surviving contemporary depictions or descriptions of these early Garter robes. The seventeenth-century antiquarian and Garter King of Arms, Elias Ashmole, identified six main components to the Garter ‘habit’ – the Garter, mantle, surcoat, hood, George and collar – noting that the first four elements dated from the reign of Edward III, while the final two were added by Henry VIII in the sixteenth century. This paper will draw on surviving Accounts of the Great Wardrobe from c. 1348-1440 to consider the Garter hood: what the garment looked like, the materials from which it was made, how it might have been worn, and its significance as an integral part of the Garter livery.

From the Phrygian Cap to the Turban: an impact of the Crusades upon representation of otherness

Dr. Tina Anderlini

Perception and representation of both past and otherness, as well as strange worlds, are subjects to discussion when it comes to medieval art. Historical realism seems not to matter. Small elements, details, are scattered in artworks to indicate to viewers that they are somewhere else or facing someone out of norm. As has pointed out by scholars like Mellinkoff or Wirth, it appears that costume is a perfect vector. Ancient and/or exotic elements are mixed with fashionable garments and indicate differences if we can recognize them. Among all elements composing a costume, headdresses seem to be preferred and most recognizable.

Early Christian art follows classical antiquity and makes a great use of the Phrygian cap, incorporating it into a complex “non-systematic system”, as Wirth termed it. But the Crusades renew this iconography, adding a new element: the turban. It takes different forms, is put on both men and women, and not only, as we may think, on Easterners. It is indeed on a Viking, in a very interesting political context. It seems this detail is a major key to read medieval images.

This paper will focus on different and meaningful examples, and on how the cap and the turban were perceived by Europeans like Joinville. How and why were they put on a lot of different people, and what these details of costume could have meant to the viewer? How did Westerners reappropriate antique and Eastern garments in iconography? How did the new garment find a place into a current of realism in medieval art? How can these details help current scholars to understand artworks and to avoid misinterpretations? How do they help us to understand the medieval world and its hierarchy?

The French Hood: royal and national identity in renaissance France

Emily Averiss

The sixteenth century saw the consolidation of royal French power under the Valois dynasty and an increasing influence in the power of queen consorts, both as political figures and cultural patrons. The visual presence of the queen, in public appearances and represented in portraiture, played a key part in defining the monarchy. What is referred to in anglophone scholarship as the ‘French Hood’ is an integral example of a garment utilized by queens of France to convey their legitimacy, continuity and magnificence. This was a round, often ornately decorated headdress with a veil covering most of the wearer’s hair.

Despite its French origin, most existing scholarship concentrates on its use in England. Yet, the ‘French Hood’, or “chaperon” in French contemporary documents, evidently played an important role in conveying French national identity. I argue that, by the mid-sixteenth century, the discernible ‘Frenchness’ of the style reinforced a queen consort’s identity as French. This was particularly vital for consorts such as Catherine de’ Medici (1519-1589), who presented herself as a legitimate ruler on behalf of her sons.

In this paper, I unpick why this headwear was seen as ‘French’ and how it came to be associated specifically with the French Royal family in the final years of the Valois dynasty. I highlight how this was used to evoke a national identity at a critical point in France’s history, and how surviving portraiture and documents evidence this throughout the sixteenth century.

Spectacles: their invention, spread and impact in the medieval period

Nick Boyle

The wearing of spectacles – or eyeglasses – in medieval times is a much-misunderstood topic. Many presume that they were not worn, merely because they do not appear in many portraits of the leaders of the age. In fact, years of research into the development of spectacles, lenses and the understanding of the eye and how it works has found that they were far more common than is generally thought. Developed in what is now Italy in the 13th century and used widely in Europe, they enabled many to continue working long after their poor eyesight prevented detailed craftsmanship and reading skills.

In this session, we will look at the written, pictorial and sculptural evidence for eyeglasses; investigate the designs and materials used to create them; and consider their impact on society up to the end of the 15th century. We will consider what had to be in place before spectacles in their bi-optic format could be invented, and learn how some lords used them to curry favour, and supported their households and tradesmen. We will also look at the evidence of spectacles coming into the British Isles, and how they were sold as part of general retail trading.

‘Ane turatis for the quen’: the headdresses of elite women in late 15th-century Scotland

Jenn Scott

This paper will explore some of the headwear worn by elite women in late 15th century Scotland. Their headdresses served not only as fashion statements but also as indicators of status, wealth, and identity. Using mostly data collected from Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland (Compota thesaurariorum Regum Scotorum), this will examine the materials used, the people wearing them and cost implications of these headdresses. The accounts provide a valuable record of the expenditures and financial priorities of the time, revealing the economic investment required to dress the royal Court. By understanding the economic aspects and the materials involved, this paper will contribute to a broader comprehension of societal norms and values in late medieval Scotland. The findings underscore the importance of fashion as a way of reflecting the wearer’s social standing and personal wealth, and its impact on the social fabric of the period. This study thus offers a new perspective on the interconnectedness of fashion, economy, and social structure in late 15th century Scotland.

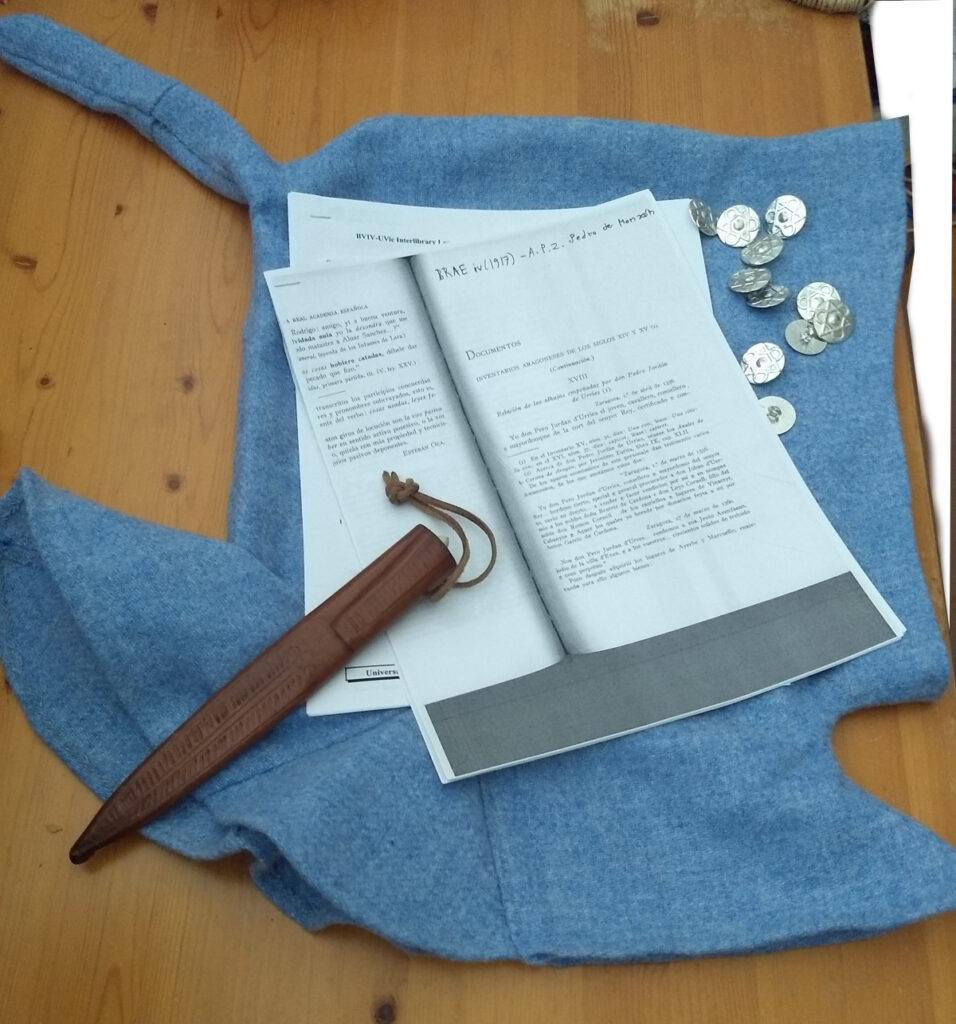

The Late Medieval Chaperon in Documents: a first cut

Dr. Sean Manning

Men and women in later medieval Europe loved to wear hoods with broad skirts or long tails. They became popular with the baggy flowing fashions around 1300, stayed in fashion with the close-fitting, narrow-waisted fashions of the middle of the fourteenth century, and mutated into strange new forms at the courts of the dukes of Burgundy. Royal decrees, guild rules, inventories, and expense accounts often mention these common garments.

Romance chaperon (and Germanic equivalents such as hood and Gugel) is a well-understood term with a consistent and specific meaning. Many surviving garments are agreed to be chaperons, and many hoods in paintings and sculptures are identified with that term. This allows dress scholars to use the three-source method and combine texts, artifacts, and artwork. Documents communicate things which are difficult or impossible to find in the archaeological record such as the materials of chaperons and their linings, their incorporation into robes (suits) cut from the same cloth, the wearing of multiple chaperons at once, and the fastening of some chaperons at the throat with buttons or hooks. The hoods from Greenland graves and Danish bogs are not a representative sample of clothes worn in urban Europe, and many questions about their last wearers will remain unanswered. Expense accounts and inventories are very clear about who owned or received what.

In the past 20 years a number of ambitious projects attempt to catalogue entire categories of evidence for clothing, such as the Tudor Tailor project on documents from Tudor England or Elizabeth Coatsworth and Gale Owen-Crocker’s book Clothing the Past: Surviving Garments from Early Medieval to Early Modern Western Europe. I do not yet have such a catalogue, so this project is a sketch of some things I have found, powered not by a card catalogue or relational database but by one human mind.